|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

Text by Robin Barefield

Photos by Mike Munsey, Robin Barefield, and Ryan Augustine

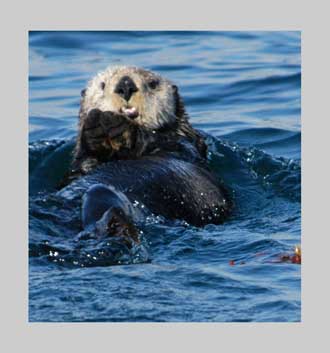

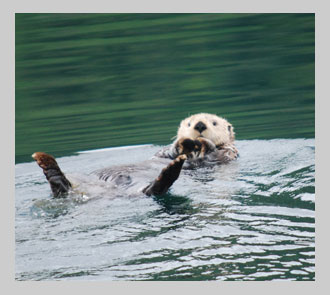

Northern Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris kenyoni) |

|

|

Sea otters (Enhydra lutris) belong to one of the four groups of former land mammals that have returned to and adapted to a life in the ocean. The other three groups are the pinnipeds (seals, sea lions, fur seals and walruses), the sirenians (manatees and dugongs), and the cetaceans (whales, porpoises, and dolphins).[1] While sea otters returned to the ocean much more recently than the other three groups, they are in at least one way better adapted than pinnipeds to a life in the sea. Seals and other pinnipeds must haul out on land or ice to give birth, but sea otters deliver their young in the ocean.[2] While sea otters are the second smallest marine mammal, they are the largest members of the mustelid family, which also includes freshwater otters, weasels, minks, skunks and badgers.[1] Sea otters may weigh as much as 100 lbs (45.5 kg). The average adult California female weighs 44 lbs. (20 kg), and the average male weighs 64 lbs. (29 kg). In Alaska, the average adult female is 4 ft. (1.2 meters) long and weighs 60 lbs. (27.3 kg), while the average adult male is 5 ft. (1.5 meters) long and weighs 70 lbs. (31.8 kg).[1,3] Sea otters are the only mustelid in the genus Enhydra, and they are significantly different from all other mustelids.[2] Sea otters are one of nine to thirteen (taxonomists disagree on the exact number) species of otters found around the world.[1] Except for sea otters and the endangered species of marine otters, all other otters live primarily in freshwater, although river otters (Lutra canadensis) travel freely between rivers and the ocean,[1] and on Kodiak, it is common to see river otters swimming near shore in the ocean. River otters and sea otters resemble each other, but sea otters are larger and weigh two to three times more than river otters. Sea otters have adapted to a life in the ocean with hind feet that are webbed to the tips of their toes and resemble flippers. River otters also have webbed feet, but they are small, making it easier for river otters to move on land, while sea otters are very clumsy out of water.[1] A sea otter’s tail is flat and looks like a paddle, while a river otter has a long, round tail that tapers to a point.[1] The claws in the forepaws of a sea otter can be extended, but those of a river otter cannot.[1] River otters swim on their stomachs, and although sea otters can also swim on their stomachs, they usually swim on their backs while paddling with their hindflippers. River otters give birth to litters of up to four pups, but sea otters, like other marine mammals, usually only give birth to a single pup.[1] There are three subspecies of sea otters. Enhydra lutris lutris ranges from the Kuril Islands to the Commander Islands in the western Pacific Ocean. The sea otters in this subspecies are the largest and have a wide skull and short nasal bones. The Southern sea otters, or the California sea otters as they are commonly called (Enhydra lutris nereis), are found off the coast of central California. Sea otters in this group are smaller and have a narrower skull with a long rostrum and small teeth. The vast majority of sea otters belong to the subspecies Enhydra lutris kenyoni, the Northern sea otters. This subspecies ranges from the Aleutian Islands to British Columbia, Washington, and northern Oregon.[2] Before the 1700's, an estimated 150,000 to 300,000 sea otters inhabited the area from northern Japan to the Alaska Peninsula and along the Pacific coast of North America to southern California.[1] Between 1741 and 1911 when sea otters were aggressively harvested for their luxurious furs, the population dropped to only 1000 to 2000 animals, and they had been eliminated from much of their original range. Many biologists believed the population was headed toward extinction.[2] In 1911, the International Fur Seal Treaty was signed by the U.S., Russia, Great Britain, and Japan, stopping the commercial hunting of sea otters, and slowly, their numbers began to increase. Sea otters began recolonizing much of their former range and were reintroduced to other areas. Sea otters now occupy about two-thirds of their historical range.[4] Counts between 2004 and 2007 estimate the worldwide sea otter population at approximately 107,000 animals.[2] Sea otter populations are considered stable in most areas, although California populations have plateaued or slightly decreased,[2] and there has been a drastic decline in sea otter numbers in southwest Alaska, from Kodiak Island through the western Aleutian Islands. This area once contained more than half of the world’s sea otters, but the population has declined by at least 55 to 67 percent since the mid 1980's, and in 2005, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed this distinct population segment as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act.[4] In 1973, the otter population in Alaska was estimated at between 100,000 and 125,000 animals, but by 2006, the population had fallen to approximately 73,000 animals, mainly due to declines in the Southwest Alaska District Population Segment.[2] The cause of this decline is unclear, but evidence suggests that it may be due to increased predation by killer whales.[4] |

|

Sea otters are well adapted to their marine environment. Their nostrils and ears can close when diving,[2] and they are able to change the refractive power of their lenses so they can see clearly in water as well as in air.[1] The skeleton of a sea otter is loosely articulated and has no clavicle, allowing the animal a great deal of flexibility when swimming and grooming.[5] A sea otter’s hind feet are flattened and webbed much like flippers, and the fifth digit on each foot is elongated, allowing the otter to swim more efficiently on its back.[5] The front paws are short and have extendible claws and tough pads on the palms, enabling the otter to grip slippery prey, and the teeth are adapted for crushing hard-shelled invertebrates.[2] Sea otters have large, lobulated kidneys that allow them to conserve water and maintain water balance while living in a saltwater environment, Their kidneys efficiently absorb water and eliminate excess salt in urea, a waste product more concentrated than sea water.[2] Sea otters are very buoyant due to their large lungs, which are two-and-one-half times bigger than those of a similar-sized land mammal.[2] |

|

|

Sea otters are not particularly streamlined, and because of this, they are the slowest swimming of all marine mammals.[1] Top speed for a sea otter is 5.6 mph (9 km/hr),[2] but speeds of 2 to 3 mph (3.2 to 4.8 km/hr) are more common.[1] Sea otters usually swim on their backs while paddling with their hindflippers, but when an otter needs to travel quickly, it swims on its stomach and undulates its entire body.[1] Sea otters are graceful in the ocean, but they aren’t built to travel on land. It is rare to see a sea otter on land, but some like to haul out on rocks, and on Kodiak, we occasionally see sea otters resting on blocks of ice in the winter. When they do travel on land, they travel at a clumsy, rolling gait or run in a bounding motion. (Photo by Ryan Augustine) |

|

Otters generally dive and feed in fairly shallow water, less than 60 ft.(18.3 m), and they normally only stay under water for one to two minutes, but they have been known to dive as deep as 330 ft. (100.58 m) and remain submerged for as long as four to five minutes. They are able to stay under water this long because of their large lungs that can store an abundant supply of oxygen, and because of their flexible ribs that allow their lungs to collapse under pressure.[1] |

|

A marine mammal must maintain a body temperature near 100° F (37.8° C), and in Alaska, where the water drops as low as 35° F (1.67° C), this can be a challenge. Other marine mammals have a thick layer of blubber to insulate themselves from the cold, but sea otters have very little fat and depend mainly on their fur to keep them warm. Sea otters have the thickest fur of any animal, with 850,000 to one million hairs per square inch (up to 150,000 per square centimeter).[6] It is their dense, beautiful fur that made them so valuable to fur traders in the 1700's and 1800's. The fur consists of two layers. Long guard hairs form the outer layer, and these provide a protective coat that keeps the underfur dry. It is this extremely dense underfur that keeps the otter warm, but to insulate efficiently, the fur must be clean, so sea otters spend a large portion of each day grooming and cleaning their fur.[1] In addition to cleaning his fur, an otter will somersault in the water and rub his body to trap air bubbles in his fur. These bubbles not only provide insulation but also help to keep the skin dry.[1] Since sea otters must have clean fur to stay warm, they are particularly susceptible to the ravages of an oil spill. If their fur becomes oiled, it loses its insulating properties. And when an otter tries to clean his oiled fur, he ingests the toxins from the oil.[3] An otter’s underfur ranges from brown to black, with guard hairs that may be light brown, silver, or black.[3] Alaskan sea otters often have lighter fur on their heads, and the fur usually lightens as an otter ages.[1] In addition to their warm fur, sea otters maintain their body heat by burning calories at a rapid rate. A sea otter’s metabolism is two to three times higher than that of a similar-sized land mammal. Because its metabolic rate is so high, a sea otter must eat 23 to 33 percent of its body weight each day. That means that a fifty-pound otter will eat 11 to 16 lbs. (5 to 7.3 kg) of food every day.[1] Sea otters also maintain their body heat by keeping their forepaws out of the water and their hindflippers folded over their abdomens when resting and floating. An otter’s paws are covered by very little fur and lose heat rapidly when submerged in cold water.[1] |

|

|

Besides being able to see well above and below water, a sea otter’s eyes are adapted to night vision or good vision in dark, murky water.[1] Nevertheless, their vision is less acute than that of a seal.[2] Sea otters have a very good sense of smell and taste, and when one otter approaches another, he sniffs or nibbles at the other’s head, abdomen, and hindflipper area.[1] Males use their noses to detect receptive females from as far as a mile (1.6 km) away.[1] Biologists believe that sea otters have average hearing,[2] and they seem most sensitive to high frequencies.[1] Sea otters have a good sense of touch. Their long whiskers can detect vibrations in the water and help them find prey, and their sensitive forepaws help them locate and capture prey.[1] Otters can be very vocal, and when a pup cries for its mother, it sounds like a seagull. Females coo when they are content, while males grunt. When frightened, adults whistle, hiss, and sometimes scream very loudly.[2] |

|

Sea otters’ diets vary not only from one location to another and in response to available prey species, but also because individual otters have different food preferences, and a mother often passes on her fondness for certain foods to her pup.[1] Sea otters usually eat benthic invertebrates, including clams, mussels, sea urchins, snails, crabs, and octopus, but they may also occasionally eat fish and even sea birds.[5] They are the only marine animals capable of lifting and turning over rocks in search of prey and the only marine mammal that catches fish with its forepaws rather than with its teeth.[2] The otter in this photo is eating a large octopus while a seagull waits for his scraps. A sea otter has a loose pouch of skin under each forleg where it can store food as it’s collected. When the otter returns to the surface, it can rest on its back and leisurely retrieve one piece of food after another from its pouch.[1] In addition to food, the sea otter also stores a rock in one of its pouches. The otter may use the rock under water to pry loose mussels or other attached bivalves or to dislodge sea urchins wedged in crevices. When floating on the surface, the otter places the rock on its chest and pounds crabs, snails, clams, and other prey against the rock to break through the tough shells. Sea otters are one of the few animals other than humans known to use tools.[1] |

|

Female sea otters reach sexual maturity and begin to breed between the ages of two to five. They may produce offspring every year until the age of twenty. Males become sexually mature between the ages of four to six years, but they often don’t have breeding territories for several years.[5] A male is most likely to mate if he can patrol and defend a territory that is favored by females. He allows females to enter and leave his territory but excludes other males. Males that don’t have territories tend to gather in large groups and swim through non-protected areas in search of a mate. Sea otters are serially polygamous. A male may form a pair-bond with a female for a few days, copulating with her several times before leaving her and forming a pair-bond with another female.[1] When a male and female form a pair-bond, they remain close to each other for several days. They seem very affectionate in their courtship, feeding, grooming, resting, and frolicking with each other, but copulation between sea otters is a rough, sometimes violent act. Copulation always takes place in the water. The female rests on her back and bends her head back, while the male gets behind her and grasps her face or nose with his teeth while the pair splash and roll on the surface. This can last for 15 to 30 minutes, and by the time it’s over, the female often has a bloody, scarred nose. Biologists believe that once a female becomes pregnant, she is no longer sexually receptive.[1] Mating can occur at any time of the year, and while the young may be born in any season, most pups in Alaska are born in the spring. As with bears, when a sea otter becomes pregnant, the implantation and development of the embryo often stops, and the embryo may not implant for several months. Scientists believe the purpose of delayed implantation in sea otters is to allow for the birth of pups when environmental conditions and food supplies are most favorable.[1] Sea otters are pregnant for four months, but because the length of the delayed implantation varies so greatly, the gestation period may last from four to twelve months.[2] |

| Sea otters give birth in the water usually to a single pup, although twins do occur, and since a mother can’t care for two pups at a time, she abandons one of the pups.[1] At birth, a pup weighs 3 to 5 lbs. (1.4 to 2.3 kg.).[5] The pup is born with eyes open and ten visible teeth.[2] The pup has a thick coat of baby fur that helps it stay afloat on the surface. The fur is so buoyant that a young pup can’t dive very well, and when it tries, it simply bobs back to the surface like a cork.[1] |

|

Sea otter mothers are normally very attentive, affectionate, and protective of their pups. A pup spends most of its time riding on its mother’s belly, and even pups six-moths of age or older and nearly as large as their mother will climb on her stomach as she appears to struggle to keep her head above water.[1] For the first two months, a pup gets nearly all of its nourishment by nursing, and while the pup will continue to nurse as long as it is with its mother, it slowly begins to add more solid foods to its diet. A sea otter’s milk is made up of twenty to twenty-five percent fat. In comparison, human milk has a fat content of three to four percent. The high fat and protein content of sea otter milk promotes rapid tissue growth, which is necessary for survival in a marine environment.[1] |

|

|

In addition to cradling her pup on her chest to keep him warm, a mother meticulously grooms her pup’s fur until the pup is three to four months old and able to groom himself. At this age, the pup is also able to swim on his back and dive with ease.[1] The mother teaches the pup how to catch and eat prey, and by the time the pup is six months old, he can capture and break open his own prey.[1] Sea otter pups remain with their mothers anywhere from three to twelve months. Alaskan pups weigh more and are able to survive on their own at a younger age than California pups. At weaning, Alaskan pups weigh 35 to 44 lbs (16 to 20 kg), while California pups weigh only 24 to 31 lbs. (11 to 14 kg). This is possibly due to a richer food supply and a less-polluted habitat in Alaska. The pup mortality rate is also much less in Alaska (15% on Kodiak Island) than it is in California (as high as 40%). Research indicates that older mothers are much more successful than younger mothers at raising pups.[1] |

|

Sea otters often float together in large groups called rafts. Except for territorial males who rest with female groups, most rafts are comprised of individuals of the same sex,[1] and mothers with pups often rest together in nursery groups.[1] Rafts usually consist of between ten and more than one-hundred otters,[3] but in Alaska, rafts with 2000 individuals have been reported.[1] Otters forage alone, but there is constant interaction between individuals in a raft. Pups and juveniles in particular spend a great deal of time playing with each other, wrestling, and leaping out of the water.[1] Male sea otters have a life span of ten to fifteen years, and females, on the average, live fifteen to twenty years.[1] Killer whales, sea lions, and sharks have been known to prey on sea otters,[2] and increased predation by killer whales has been blamed for the precipitous decline of otters in southwest Alaska.[4] Bald eagles may prey on pups, and on land, sea otters may be attacked by coyotes and bears.[2] |

|

By far, however, the greatest threats to sea otters are human-related. Sea otters are very efficient at finding and eating shellfish, and they are able to reduce populations of abalones, clams, and sea urchins to the point where a commercial fishery for these species is not viable in areas with large sea otter populations. This creates a conflict between sea otters, fishermen, and fish and wildlife managers.[2] Since sea otters are dependent on their fur to keep them warm and insulated from the cold ocean water, and since they must continually groom their fur to maintain its insulating properties, they are extremely vulnerable to the effects of pollution. When an otter’s fur is soiled with oil or another pollutant, the fur becomes matted, and it can no longer keep the animal warm. This can lead to hypothermia and death from exposure. When the otter tries to clean his fur to remove the pollutant, he ingests the toxin, which is also often fatal.[1] When the Exxon Valdez struck a reef in Prince William Sound in 1989 and spilled eleven million gallons of crude oil, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimated that approximately 3,905 sea otters were killed, but some estimates put the number as high as 11,257 otters.[4] Sea otters are considered a “Keystone” species, meaning that they effect the ecosystem to a much greater degree than their numbers would suggest.[2] Sea otters protect kelp forests by eating herbivores such as sea urchins that graze on the kelp. In turn, the kelp forests provide food and cover for many other species of animals, and kelp forests play an important role in capturing carbon and reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.[6] |

|

Literature Cited 1. Riedman, Marianne (1997). Sea Otters. Monterey Bay Aquarium Foundation. ISBN: 1-878244-03-5. 2. Sea Otter. Wikipedia. Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/sea_otter. 3. Sea Otter Facts. Available at: www.seaotter-sealion.org/seaotter/factsseaotter.html.

4. Sea Otter Population Status of the Northern Sea Otter. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Marine Mammals Management. Available at: www.fws.gov/alaska/fisheries/mmm/seaotters/history.htm .

5. Northern Sea Otter in Alaska (Enhydra lutris kenyoni). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wildlife Biologue. Available at: www.fws.gov/alaska/fisheries/mmm/seaotters/pdf/biologue.pdf .

6. Sea Otter Fact Sheet. Available at: www.defenders.org/sea-otter/sea-otter/basic-facts .

|

Copyright 2012 Munsey's Bear Camp