|

The bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) is only found in North America. Its range stretches from northern Mexico to Canada and Alaska and covers all of the continental United States (Wikipedia. Bald Eagle). Due to a variety of factors, including use of the pesticide DDT, by the 1950's bald eagles were nearly extinct in the contiguous United States. The 1940 Bald Eagle Protection Act prohibited commercial trapping and killing of bald and golden eagles, and more significantly, DDT was banned in 1972 when it was proven that the pesticide interfered with the eagle’s calcium metabolism, causing either sterility or unhealthy eggs with brittle shells (Wikipedia. Bald Eagle). In 1973, Congress passed the Endangered Species Act, and the bald eagle was listed as an endangered species (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). In 1995, when eagle populations in the continental U.S. began to rebound, the bald eagle was removed from the endangered species list and transferred to the threatened species list. On June 28, 2007, bald eagles were removed from the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife (Wikipedia. Bald Eagle).

|

|

| While Alaska’s eagles were never threatened by the use of DDT, Alaska has its own unique, nefarious history with bald eagles. In 1917, commercial salmon fishermen convinced the Alaska Territorial Legislature that eagles were killing large numbers of salmon and were therefore competing with the fishermen’s livelihood. This claim was later shown to be false, but the legislature enacted a bounty system, paying two dollars for each pair of eagle legs turned in. This bounty system lasted for thirty-six years and led to the killing of a confirmed 120,195 eagles, plus countless others for which no bounty was paid (Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game. Bald Eagle). The bounty system ended in 1953, and when Alaska became a state in 1959, its bald eagles were officially protected under the Federal Bald Eagle Protection Act of 1940. Alaska’s eagle population is now considered very healthy, and it is estimated that one half of the world’s 70,000 bald eagles live in Alaska (American Bald Eagle Information). Twenty-five-hundred bald eagles reside on the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge(Joling, 2011). |

TAXONOMY

The genus Haliaeetus, the sea eagles (in latin, hali means salt and aeetus means eagle), includes eight of the sixty species of eagles. The sea eagles live along sea coasts, lakes, and river shores (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988). Haliaeetus leucocephalus (leuco means white and cephalus means head) consists of two subspecies. The southern bald eagle, Haliaeetus leucocephalus leucocephalus, is found from Baja California and Texas to South Carolina and Florida, south of 40 degrees north latitude. The northern bald eagle, Haliaeetus leucocephalus alascanus occurs north of 40 degrees north latitude (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). Northern bald eagles are larger than their southern cousins.

|

|

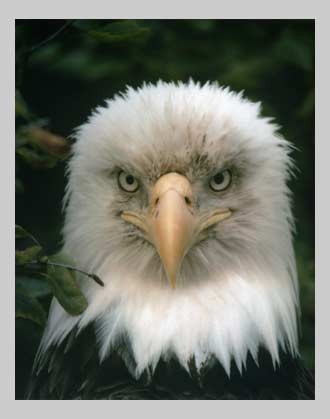

The bald eagle is named for its white head. “Bald” in this case means white not hairless (Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game. Bald Eagle). Both adult female and male bald eagles have a blackish-brown back and breast; a white head, neck, and tail; and yellow feet and beak. Immature bald eagles have a dusky brown head and tail, a brown bill, and blotches of white or cream on the bodies and wings. It takes five years for immature eagles to obtain adult coloration (Gordon, 1991).

|

|

Female bald eagles are slightly larger than males. Males range in body length from 30 to 34 inches (76.2 to 86.4 cm), while females measure 35 to 37 inches (89 to 94 cm). The wingspan of a male stretches from 72 to 85 inches (182.9 to 215.9 cm), while a female’s wingspan ranges from 79 to 90 inches (200.7 to 228.6 cm) (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). Bald eagles weigh between 8 and 14 lbs. (3.6 to 6.4 kgs.) (Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game. Eagles).

The skeleton of a bald eagle weighs 0.5 lbs (250 to 350 grams), which is only 5 to 6% of the total weight of the bird. The bones are extremely light, because they are hollow, and the feathers weigh twice as much as the bones (American Bald Eagle Information).

The bald eagle’s average body temperature is 106 degrees Fahrenheit (41 degrees Celsius). They don’t sweat, so they cool themselves in other ways, such as panting, holding their wings away from their bodies, and perching in the shade. In cold weather, an eagle’s skin is protected by feathers which are lined with down. Their feet consist mainly of tendon and are cold-resistant, and there is little blood supply to the bill, which is mostly nonliving material (American Bald Eagle Information).

|

|

The beak, talons, and feathers of an eagle are made of keratin, the same material as in our fingernails and hair. Because of this, the beak and talons continuously grow and are worn down through usage. An eagle’s beak can be used as a weapon and is sharp enough to slice skin, but is also delicate enough to groom a mate’s feathers and feed a chick. The talons are important for defense and hunting (American Bald Eagle Information).

An eagle’s call is a high-pitched, whining scream that is broken into a series of notes. They don’t have vocal cords, so sound is produced in a bony chamber called the syrinx, located where the trachea divides before the lungs (American Bald Eagle Information). Scientists have differentiated four different calls. Eagles are most vocal when they are threatened, annoyed, or mating (Gordon, 1991).

Listen to the following video to hear an eagle’s call.

|

|

Bald eagles have 7000 feathers (http://www.baldeagleinfo.com). Feathers protect them from both heat and cold and offer a barrier to snow and rain. They have several layers of feathers that tightly overlap and provide a solid covering. It is because of this coat of feathers that eagles are able to spend winters in extremely cold climates. Depending on the ambient temperature, an eagle can rotate its feathers to reduce or increase their insulating effect (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). They puff up their feathers for a variety of reasons, including preening, to insulate themselves from cold temperatures, to make themselves appear larger when threatened, and when they’re sick (American Bald Eagle Information).

Feathers are of course also necessary for flight and for gliding and soaring. Like the bones, the feathers are hollow and lightweight, but they are structurally very strong. The primaries, the large feathers along the tips of the wings, provide lift and are the main controls for flight. An eagle twists these feathers to brake, turn, and maneuver. The tail feathers are also important for flying, maneuvering, and landing and for stabilizing an eagle when it dives toward prey (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

|

SENSES

The eyes of an eagle are larger than those of an adult human (Wright and Schempf, 2010), and an eagle’s eyesight is at least four times sharper than that of a human with perfect vision (American Bald Eagle Information). An eagle flying at an altitude of several hundred feet can spot a fish under water. The eyes are protected by a nictating membrane (Wright and Schempf, 2010), and each eye has two fovae or centers of focus that allow the bird to see both forward and to the side at the same time (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). Eagles have binocular vision, which allows them to perceive depth and is particularly useful when diving at prey. The lens of the eye is soft, allowing it to change from near to far focusing and back again (Gordon, 1991).

While not as outstanding as their vision, eagles do have good hearing and use it to locate prey or other birds (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

|

|

If you look up on a windy day on Kodiak Island, you will likely see several eagles soaring high in the sky. Bald eagles are built for flight, particularly for soaring and gliding. An eagle expends a great deal of energy flapping its large wings, so to conserve energy when gaining and maintaining altitude, it utilizes thermal convection currents or “thermals”, which are columns of warm air generated by terrain such as mountain slopes (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988). It has been estimated that a bald eagle can reach flying speeds of 35-43 mph (56-70 kph) when gliding and flapping and 30 mph (48 kph) while carrying a fish (Wikipedia. Bald Eagle). While not known as particularly fast fliers, eagles can soar and glide for hours at a time (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

The construction of the wings and tail make soaring and gliding possible. The wings are long and broad and are covered by a layer of lightweight feathers arranged to streamline the wing. The primary feathers, or primaries, provide lift and control an eagle’s flight during turning, diving, and braking. An eagle can tilt and rotate individual feathers to maneuver and brake. The tail also assists in braking and stabilizes the eagle when it dives toward prey. While soaring, tail feathers spread wide to maximize surface area and increase the effect of updrafts and thermals (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

When an eagle finds an air current or a thermal, it can gain altitude without flapping its wings. If it is dead calm with no air currents moving up or down, eagles cannot soar, and that is why you see more eagles soaring on windy days or sunny afternoons and sitting on their perches on calm, cool mornings (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988).

When a young eagle first leaves the nest, its wing and tail feathers are longer than those of an adult. As an eagle matures, its wing and tail feathers become shorter and narrower with each successive molt (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988). The larger wings of a juvenile make it easier for the bird to catch an updraft or weak thermal and to fly slower and in tighter circles than an adult. The down side of the larger wings and tail is that the juvenile rises slower, sinks faster, and cannot soar as far as the adult. Adult bald eagles are able to flap their wings faster and fly at a greater speed than immature eagles, making them more efficient at chasing down live prey (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988).

Female bald eagles are larger than males, and while their wings are also slightly larger, their increased size does not make up for the weight difference. Therefore, females require more wind or stronger thermals than males to effectively be able to gain altitude and soar. Since thermals are weaker during the morning and evening hours, females are more likely to remain on their perches during these times and soar when it’s windy or in the afternoon when thermals are stronger (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988).

|

| An eagle’s large wings make landing and takeoff tricky, and landing on a perch is something eagles manage to do gracefully only after much practice (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988). A newly-fledged juvenile looks very awkward when it tries to land on a perch and may even crash land or swing upside down if it grabs the perch while it still has too much forward momentum. |

|

|

|

Rising on thermals, an eagle can gain altitude until it is only a speck in the sky, and then it soars until it sees prey and can swoop down and make a kill (Gordon, 1991). When an eagle spots a fish from the air, it begins to glide toward the water. As it nears its prey, it extends its legs and opens its talons. It soars just over the surface of the water and then plunges its legs into the water. The talons strike the fish, and the eagle immediately closes them, driving them deep into its prey. The eagle then flaps its wings to pull the fish out of the water and maintain enough speed to remain airborne. If the eagle cannot lift the fish, the bird may be dragged under water and forced to swim for shore (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). Eagles are strong swimmers, but if the water is cold, they may be overcome by hypothermia and drown (American Bald Eagle Information).

|

|

It is a common misconception that once an eagle grasps its prey with its talons it can’t let go. While eagles can lock their talons, it is a voluntary action. An eagle can release a fish that is too heavy for it to lift, but sometimes it holds on anyway, perhaps deciding that the prize is worth the swim to shore (Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game. Eagle flight and other myths. Eagles don't eat children or pets).

Biologists estimate that an eagle can only lift a maximum of four to five pounds, but since lift is dependent on both wing size and air speed, the faster the eagle flies, the greater its lift potential. An eagle that lands to grab a fish and then takes off again can manage less of a load than one that swoops down at a high rate of speed and plucks its prey from the water. Speed and momentum allow the eagle to carry more weight (Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game. Eagle flight and other myths. Eagles don't eat children or pets).

An adult bald eagle needs between 0.5 lbs (.23 kg.) and1.5 lbs (.68 kgs) of food per day. A study done in Washington found that an eagle needs to consume between 6% and 11% of its body weight per day. If an eagle eats a 3 lb. (1.4 kg) fish one day, though, it doesn’t need to eat again for a few days (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988). Bald eagles living in coastal Alaska feed mainly on fish such as herring, flounder, pollock, and salmon. They may also prey upon sea birds, small mammals, sea urchins, clams, crabs, and carrion (Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game. Eagles).

In the summer and fall on Kodiak Island, eagles congregate along salmon streams or near the ocean where salmon are likely to school. Large numbers of eagles can also be observed near fish canneries where they feed on the fishy discharge from the processing plants. Both mature and immature eagles feed on carrion, but research indicates that young eagles are more dependent on carrion, and they eat carrion while they develop and hone their hunting skills (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). Adults, on the other hand, more actively hunt live prey, particularly fish.

The bill and neck muscles of a bald eagle are adapted to allow the bird to quickly gorge itself. An eagle can eat a 1 lb. (.45 kg) fish in only four minutes, and it can hold onto a fish with one talon while it grips its perch with the other talon and tears apart the fish with its bill. (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

|

|

It is generally believed that bald eagles mate for life, but if one member of the pair dies, the surviving member will usually find a new mate within a year. There is also evidence that a pair that does not produce offspring after several years may change mates (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

In the spring, bald eagles perform aerial displays that are magnificent to watch, but biologists have a tough time differentiating between the aerial acrobatics of courting displays and those of aggression, and there is much speculation that the two behavioral displays may be closely related. During a courtship flight, an eagle pair may dive at each other and then turn and touch talons in mid-air. Occasionally, the talons of both eagles will lock briefly, causing both birds to spiral downward in a cartwheeling motion. Cartwheeling is usually a display of aggression, but it is also sometimes seen during courtship (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). Other less-aggressive courtship displays have been observed in captive eagle pairs, where the male and female frequently perch beside each other and stroke and peck at each other’s bills. They also use their bills to stroke the heads, necks, and breasts of their mates (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988).

Copulation usually takes place at the nest site. Sometimes the male initiates the act, but the male must be careful approaching the larger female, and occasionally, the female injures or even kills the male (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). In most cases, the female initiates mating. She bows her head, spreads her legs, and raises her tail. The male then approaches the female with his tail raised. The female emits a single-note call, and the male clenches his talons so he won’t hurt his mate and then climbs on her back. He lowers his tail and cloaca to meet the female’s as she raises her tail and cloaca. The male passes semen to the female and then steps down. Both eagles stand up and usually emit a simultaneous call (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). Copulations occur often during the breeding season but slow down once the eggs are laid and stop after the eggs hatch (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

Research indicates that eagles in the wild in healthy populations do not breed until they are six years old or older. Eagle populations in these areas consist of breeding adults, non-breeding adults, and non-breeding immatures. In areas saturated with eagles, such as on Kodiak Island, more than 50% of the population may be non-breeders. In disturbed populations with lots of unused nesting habitat, younger birds and even immature eagles may breed (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988).

In a dense population, a nesting site is valuable real estate, and once an eagle pair is lucky enough to get a nesting site, they must defend their territory and hold onto it (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988). On Kodiak, bald eagle pairs remain near their nests all year, probably to ward off would-be interlopers from claiming their territory.

|

|

Bald eagles build the largest nest of any North American bird. The nest may be as large as 8 ft. (2.44 m) across and weigh as much as one ton (907 kgs) (Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game. Eagles). They often use and add to the same nest every year, which causes the nest to grow in size over time (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

Bald eagles build their nests in very large trees near the water. In Alaska, nests are usually found along saltwater shorelines or rivers, and in many parts of Alaska, eagles nest in old-growth timber (Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game. Eagles). On Kodiak Island, eagles prefer to nest in black cottonwood trees, but in areas where black cottonwood trees are not available, nests can be found on rocky cliffs or at the bases of alder trees on cliffs along the coast (Suring, 2010).

The nest is usually built in the crotch in the last set of branches one-third to one-quarter of the way down from the top of the tree (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). Eagles tend to nest in trees with fairly sparse foliage near the edge of a habitat, so they can fly to and from the nest without having to fly through a canopy of trees (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

The nests are built of sticks, and each year the eagle pair adds new branches and other vegetation to the nest to cover over food remains, feathers, and other debris left from the previous year (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). Branches and twigs are placed on the edge of the nest, while softer vegetation such as leaves, grass, and moss are placed in the center (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). Eagle pairs continue to add branches, moss, and grass to their nests all summer until the chicks are nearly grown. Researchers believe the reason for this may simply be to keep the nest cleaner. Waste, rotting fish, and even the bodies of chicks that have died in the nest are not tossed out of the nest but are buried by moss, grass, and other greenery. It is important to keep the nest clean so the chicks are not infested by parasites (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988).

An eagle pair usually uses a nest until either the eagles die or something happens to the nest or the tree holding the nest (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). An eagle pair may build two, three, or even four nests in their breeding territory, and scientists are unsure what the purpose is for these multiple nests (Gordon, 1991). The average distance between nests is usually 1 to 2 miles ( 1.6 - 3.2 km), but nest sites are often closer to each other in areas where food is plentiful (Gordon, 1991). A 2007 nesting and productivity study on the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge identified 1141 nests with 439 (38%) of those nests active. This was down from a 55% occupancy rate found in a 2002 study. Of the 439 active nests in 2007, 208 of the nests (48%) were successful in producing young. The researcher suspected that the harsh spring weather in 2006 and 2007 may have contributed to the reduction of nesting effort (Zwiefelhofer, 2007).

Nesting and breeding bald eagles are territorial and defend their nests from other animals, including other eagles. Adults spend much of the day perched in prominent trees near the nest, perhaps to make themselves more visible to intruders. A resident eagle will warn an approaching eagle with a loud call consisting of grunts followed by a high-pitched screech. Sometimes the resident eagle will quietly escort the intruder out of the area, but occasionally, one of the two birds will attack the other, resulting in a display known as cartwheeling, where one eagle descends on the other eagle, and the other bird rolls onto its back while both eagles grasp talons. The two birds then tumble to the ground and separate just before crashing (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988).

|

|

|

Bald eagles lay their eggs in mid to late May in southern areas of Alaska, although one study in Southeastern Alaska indicated that they may lay their eggs as late as early June (Gende, 2010). The female lays between one and three off-white-colored eggs in a span of one to three days. The eggs range in size from 2.76 inches by 2.09 inches (70mm by 53 mm) to 3.31 inches by 2.36 inches (84 mm by 60mm) (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997)

|

|

The eagle pair begins incubating the eggs as soon as they are laid. The male and female share the incubation duties, and each mate hunts for its own food (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). It has been estimated that for 98% of the day, either the male or female sits on the eggs. The incubating bird stands up about once per hour and may change positions (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988). A study at several nesting sites on Admiralty Island in Southeast Alaska found that eggs were incubated for 95% of the daylight hours with females sitting on the eggs 53% of the time, and males tending the eggs 42% of the time. Brooding time dropped to 79% of the day for the first 10 days after the eggs hatched and by 41 to 50 days after hatching, the brooding time decreased to only 6% of each day. Brooding time increased when it was rainy and decreased when it was sunny (Cain, 2010). The incubation period takes 34 to 36 days. Since individual eggs may be laid a few days apart, they will not all hatch at the same time (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

The hatching process is slow and arduous. It takes chicks twelve to forty-eight hours to fully emerge from the egg (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). The chick makes the first crack in the shell with its egg tooth, a small, hard bump on the top of the bill. The chick then rests awhile and then chisels around the large end of the egg. The chick eventually pushes off the end of the egg and wriggles out of the shell. The egg tooth dries up and falls off four to six weeks after hatching (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

During hatching, a chick must undergo several physiological adaptations. Before it hatches, a chick absorbs oxygen through the shell by way of the mat of membranes under the shell. During the hatching process, the chick must cut the blood supply to these membranes and trap the blood within its body. At the same time, it must also inflate its lungs and begin breathing air once it has cracked the shell. The chick must also absorb the yolk sack into its body and seal off the umbilicus (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

Newborn chicks are wet, exhausted, nearly blind, and extremely needy. Since a newly-hatched chick can’t regulate its body temperature, the parents must keep it warm. The chick is covered with pale gray down. The skin and scales of the legs are bright pink, the bill is a grey-black with a white tip, and the talons are flesh-colored. After the first week, the legs begin to turn yellow (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988).

Eagles lay one to three eggs, but at the most, usually only one or two chicks survive. Survivability is directly correlated to age. The first chick to hatch will be one to two days older than its siblings, so it will be larger and stronger and able to out-compete its nestlings if food is limited. If a brood has three chicks, the smallest chick usually dies within a week of hatching. Death is not normally caused by injuries from fighting with its siblings, but the chick simply starves to death because the older nestlings get all the food. The older chicks peck the young chick into submission to prevent it from eating enough to survive. This ensures that there will be enough food for the surviving chicks (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988).

|

|

Three weeks after hatching, chicks molt to a thicker, darker down that remains until the first set of feathers develop. At this stage, one of the parents remains near the nest to shelter the chicks from direct sunlight, inclement weather, and anything else that can harm them (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

|

|

|

When an eagle chick first hatches, its bill and eyes are dark-colored. Over the course of three to four years, the bill lightens to a swirl of shades of brown then to yellow-brown, and finally to bright yellow. The eyes lighten to buff yellow by one-and-one-half years, light cream by age two-and-one-half, and pale yellow by three-and-one-half (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988).

As the chicks develop feathers and grow, the parents spend less time at the nest and more time hunting for food. The chicks grow very rapidly as long as the parents can provide sufficient food. If the parents are unable to find enough food, the smallest chicks may die (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997).

At one-and-one-half to two weeks, most young eagles weigh 1 to 2 lbs. (500 to 900 grams). Between 18 - 24 days, chicks gain 4 ozs. (100-130 grams) per day, a faster weight gain than at any other stage of their development (Gordon, 1991). Eaglets begin feeding themselves around the sixth to seventh week, and by eight weeks, they can stand and walk around the nest. At sixty days, eaglets are well-feathered and have gained 90% of their adult weight. Large nestlings consume nearly as much food as adults (Gordon, 1991).

Chicks remain in the nest for ten to twelve weeks. A week or two before they fledge, they can be seen on the rim of the nest exercising their wings and holding onto the nest with their talons. They flap their wings and may even lift off the nest while exercising. A chick may fall or be blown off a nest while exercising, and if it can’t make it to another branch, it may fall to its death (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). It has been estimated that one in seven eaglets fledges prematurely, either falling or jumping from the nest before it can fly (Gordon, 1991).

Once their muscles and wings are strong enough, eaglets are ready to leave the nest. What prompts the chicks to fledge is a matter of speculation, but at some point, the parents cut back on the amount of food they provide their young, and they may even use food to lure the chicks away from the nest (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997)). Males fledge at an average of 78 days, and females fledge at an average of 82 days (Gordon, 1991). Research in Southeast Alaska shows that fledging there occurs on average in mid-August (Gende, 2010).

The first several flights of a fledgling are very clumsy, and their first several landings are usually crash landings. Juvenile birds have longer wings and tails than adults, and this makes learning to fly easier for them (Wolfe and Bruning, 1997). As an eagle matures, with each molt, the wings become shorter and narrower, and the tail gets shorter.

Immature eagles usually stay within a half-mile radius of the nest for the first six weeks after fledging, and they may even continue to receive food from their parents during this time. Eight to ten weeks after fledging, they seem to develop a stronger instinct to move (Gordon, 1991).

As immature eagles grow, their body coloration changes and they molt and replace feathers each summer. When they first fledge, juveniles are dark brown, except under the wings which are mostly white. As juveniles mature, their feathers become a mottled brown and white. By three-and-one-half years, the head and tail are nearly all white, and by four-and-one-half, immature eagles are nearly indistinguishable from adults (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988).

|

|

Eagles are well-insulated by their feathers and are very good at regulating their body temperature. Unlike many birds, they do not need to migrate to warmer areas each winter, but in many parts of the country they do migrate, sometimes long distances, in response to varying food supplies (Gerrard and Bortolotti,, 1988). Due to its abundant year-round food supply, Kodiak has a non-migratory eagle population (Zwiefelhofer, 2007). Furthermore, hundreds of eagles from the Alaskan mainland migrate to Kodiak for the winter months (Joling, 2011). The canneries and fish processing plants in the town of Kodiak are a major draw for these birds, and in the winter months, hundreds of eagles can be seen in town perched in trees, on cannery rooftops, on the edges of dumpsters, and even on pickup trucks. In Uyak Bay, we notice that the nesting eagles stay near their nests all winter, feeding on fish and winter-killed deer among other things.

|

|

|

Since the ban on DDT and related pesticides in 1972, bald eagle populations around the country have rebounded to some degree. The bald eagle population in Alaska is healthy and stable and has never been listed as endangered or threatened by the Federal Government. Eagles in Alaska never suffered the scourge of DDT poisoning, and even now in most areas, they live in a relatively contaminant-free environment (Thomas, 2010).

|

|

The Bald Eagle Protection Act passed in 1940 imposes a fine of $10,000 and two years imprisonment for anyone who harms a bald or golden eagle. It is illegal even to have an eagle feather in your possession without a proper permit (Gordon, 1991). Nevertheless, humans are still responsible for many bald eagle deaths. Of the 1428 bald eagles necropsied by the National Wildlife Health Center from 1963 to 1984, 23% died from trauma, primarily impact with wires and vehicles, 22% died from gunshot wounds, 11% died from poisoning, 9% from electrocution, 5% from emaciation, 2% from disease, and the cause of death was undetermined in the other 20% of the necropsies (Wikipedia. Bald Eagle). In Alaska, necropsies on 344 bald eagles from 1975 to1989 revealed that 24.7% died from trauma, 17.5% from electrocution, 15.4% from emaciation, 12.8% from gunshot wounds, 7.3% from poisoning, 3.8% from infectious disease, 2% from trapping, and 16.5% from other causes (Thomas, 2010). On Kodiak, Refuge biologists have recovered eagles that have starved to death, eagles killed by airplanes and cars, eagles caught in traps, and eagles oiled by fish slime or fossil fuels (Joling, 2011). The Exxon Valdez oil spill was responsible for killing hundreds of eagles in Alaska.

In January 2008, fifty eagles swooped down on a dump truck filled with fish guts outside a Kodiak seafood processing plant. Twenty of the eagles were drowned or crushed, and the rest were so slimed they had to be cleaned (Halpin, 2008). Bait left unattended on a fishing boat can cause a frenzy when eagles land and start fighting over their find. If their feathers become oiled by the fish slime, they become less-waterproof, and then if the eagle falls into the water, it is more susceptible to hypothermia (Joling, 2011).

In 2009, the Kodiak Electric Association (KEA) erected three wind turbines on Pillar Mountain near the town of Kodiak and added an additional three turbines in 2012. At first there was concern that the turbines would be a danger to eagles, since turbines elsewhere in the U.S. kill an estimated 573,000 birds a year (Brooks, 2013). KEA funded a study to address the concerns, and it was determined that eagles went out of their way to avoid crossing the ridge among the turbines (Sharp et al., 2010). No eagles were killed during the study, and according to avian biologist, Robin Corcoran, she has never received a report of a dead eagle near the turbines (Brooks, 2013).

Eagles do die from electrocution on Kodiak. Many of the power poles near town are fitted with devices designed to protect eagles, but in January 2011, an eagle was electrocuted when she landed on the lowest of three cross bars on a power pole. That particular cross bar did not have a protective device, because utility authorities believed there was not enough room for an eagle to land on it. The eagle had been banded by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, so biologists knew she was 25 years old, the second-oldest bald eagle documented in Alaska, and one of the oldest-documented eagles in the country (Joling, 2011).

While these manmade disasters are tragic, they are fairly uncommon and don’t appear to be a threat to Alaska’s bald eagle population. A greater and less-obvious threat is the destruction of eagle nesting habitat by logging and commercial and residential development. Eagles tend to nest in large, old trees that are not easily or quickly replaced once they are removed (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988).

Once an eagle attains its adult plumage, it is impossible to determine its age unless it has been leg-banded by biologists. For this reason, there is limited data on the life span of bald eagles. It is believed that 50-70% of all juvenile bald eagles die in their first year, and as many as 90% die before they are fully mature. (Gordon, 1991). Eagles in captivity may live 40 to 50 years (Gerrard and Bortolotti, 1988). The oldest documented was an eagle in Stephentown, New York that lived to be 48 years old (American Bald Eagle Information). The average life span in the wild is believed to be 15 to 20 years. The oldest documented wild eagle was a 32-year-old bird from Maine. Alaska’s oldest eagle was a 28-year-old from the Chilkat Valley, and a 25-year-old is the oldest documented on Kodiak (Joling, 2011).

|

|

Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucephalus). Available at: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=baldeagle.main

Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Eagles. Available at: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/static/education/wns/eagles.pdf

Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Eagle flight and other myths. Eagles don’t eat children or pets. Available at: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_id=343

American Bald Eagle Information. Available at: http://www.baldeagleinfo.com

Brooks, James (2013). Bird fears overblown in Kodiak. Kodiak Daily Mirror. Vol. 75 No. 106 May 30, 2013 pgs. 1 and 3.

Cain, Steven L. (2010). Time budgets and behavior of nesting bald eagles. Bald Eagles in Alaska. Hancock House Publishers. Blaine, Washington. ISBN: 97800-88839-969-9. Pgs. 73-94.

Gende, Scott M. (2010). Perspectives on the breeding biology of bald eagles in Southeast Alaska. Bald Eagles in Alaska. Hancock House Publishers. Blaine, Washington. ISBN: 97800-88839-969-9. Pgs. 95-105.

Gerrard, J.M. and Bortolotti, G.R.(1988). The Bald Eagle Hunts and Habits of a Wilderness Monarch. Smithsonian Instution Press. Washington D.C. ISBN: 0874-451-2.

Gordon, David G.(1991). The Audobon Society Field Guide to the Bald Eagles. Sasquatch Books. Seattle, Washington. ISBN: 0-9012365-46-3.

Halpin, James (2008). Hungry eagles die in fish-guts dump truck. Anchorage Daily News. Published January 11, 2008. Available at: www.adn.com/2008/01/11/262390/hungry-eagles-die-in-fish-guts.html

Joling, Dan (2011). Band confirms dead eagle as one of Alaska’s oldest. Anchorage Daily News. Published February 13, 2011. Available at: www.adn.com/2011/02/13/1701110/band-confirms-dead-eagle-as-one.html

Sharp, L, Herman, C., Friedel, R, Kosciuch, K., and MacIntosh, R. (2010). Comparison of pre- and post- construction bald eagle use at the Pillar Mountain Wind Project, Kodiak, Alaska, Spring 2007 and 2010. Powerpoint Presentation for the Wind Wildlife Research Meeting VII, October 19-21, 2010. Available at: http://nationalwind.org/assets/research_meetings/Research_Meeting_VIII_Sharp.pdf

Suring, Lowell H.. (2010). Habitat relationships of bald eagles in Alaska. Bald Eagles in Alaska. Hancock House Publishers. Blaine, Washington. ISBN: 97800-88839-969-9. Pgs. 106-116.

Thomas, Nancy J. (2010). Causes of mortality in Alaskan bald eagles. Bald Eagles in Alaska. Hancock House Publishers. Blaine, Washington. ISBN: 97800-88839-969-9. Pgs. 138-149.

Wikipedia. Bald Eagle. Available at: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bald_Eagle

Wolfe, Art and Bruning, Donald Bald Eagles Their Life and Behavior in North America (1997). Crown Trade Paperbacks. New York, New York. ISBN: 0-517-88-163-2.

Wright, Bruce A. and Phil Schempf (2010). Introduction. Bald Eagles in Alaska. Hancock House Publishers. Blaine, Washington. ISBN: 97800-88839-969-9. Pgs. 8-18.

Zwiefelhofer, Denny (2007). Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge 2007 Bald Eagle Nesting and Productivity Survey. Report for the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge. Available at: http://www.arlis.org/docs/vol1/213371161.pdf

|

Copyright 2012 Munsey's Bear Camp

|