|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

The Sitka black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus sitkensis) and the Columbia black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus) are subspecies of the much larger mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus). The Columbia black-tailed deer is found from northern California to the Pacific Northwest and coastal British Columbia.[1] The Sitka black-tailed deer is native to the coastal rain forests of Southeast Alaska and north-coastal British Columbia. Sitka black-tails have been successfully transplanted near Yakutat and on Kodiak and Afognak Islands.[2] Twenty-five Sitka black-tailed deer were introduced to the north end of Kodiak Island in three transplants from 1924 to 1934, and another nine deer were introduced in 1934.[2] The deer population has since spread to most areas of the Kodiak archipelago, and despite the limited gene pool, the population appears to be healthy. The size of the deer population fluctuates from year to year depending on the harshness of the winter, but biologists estimate there are approximately 70,000 deer on the archipelago.[3] |

|

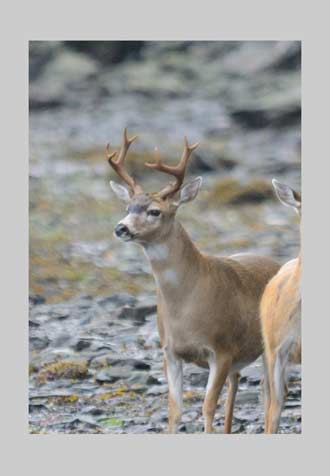

Sitka black-tailed deer are smaller, stockier, and have a shorter face than Columbia black-tails. An average adult doe weighs 80 lbs., while an average buck weighs 120 lbs. Much larger bucks weighing as much as 200 lbs. have been reported.[2] The summer coat of a Sitka black-tail is light reddish brown, while the winter coloration is dark brownish gray.[2] The antlers are fairly small compared to other species of deer and typically have three or four points on either side, including the eye guards.[4] A very large buck might have five points on each side, including the eyeguards. |

|

|

Deer antlers grow at an amazing rate. Biologists have determined that white-tailed deer antlers can grow as much as ½ inch (1.27 cm) per day during their peak growth.[5] Antler size is dependent on age, nutrition, and genetics. Antlers are made from bone, and they develop from the pedicle on the frontal bone of the skull.[6] Male fawns produce “button” antlers at the age of four to five months, and they begin growing their first noticeable antlers the following year.[6] A young buck’s first antlers may be only single spikes, but antler size usually increases with age until they reach a maximum size.[6] Antler growth requires a great deal of energy, so antler size is dependent on good nutrition and environmental conditions. A buck may produce smaller antlers the year following an extremely harsh winter. Bucks begin to grow a new set of antlers in the late spring, because the increased daylight in the spring stimulates the hormones that regulate antler growth. During the spring and summer, antlers receive a rich supply of blood and are covered by a fine membrane called “velvet”.[6] At this time, the antlers are very fragile and are vulnerable to cuts and bruises. By August, antler growth slows, and they begin to harden. A few weeks later, antler growth ceases, blood flow to the antlers stops, and the velvet dries up and falls off. Bucks then retain these hard, polished antlers throughout the mating season. After the mating season, cells start to de-mineralize the bone between the pedicle and the antler, weakening the connection between the skull and the antler, and the antler falls off..[6] On Kodiak, deer normally begin dropping their antlers from mid to late December. |

|

While no one knows why bucks grow antlers, several theories have been proposed: (1) A buck with large antlers may signal to a potential mate that he is healthy and possess good genes.[6] (2) Antlers may be used as a weapon during the breeding season to establish dominance between males.[6] (3) The size of the antlers alone may display age-related dominance without the males having to fight. Although, current research does not support this theory.[6] (4) Deer may use antlers to defend themselves against predators. Although, this would only be beneficial for bucks, since does don’t have antlers.[6] It is likely that a combination of two or more of these theories point to the true purpose of antlers. |

|

|

|

During the summer, Sitka black-tailed deer feed on herbaceous vegetation and the leaves of shrubs. During the winter when there’s snow on the ground, their diet is restricted to woody browse, which is not an adequate diet to sustain the deer over a long period of time.[4] Oddly enough, in the spring, deer may eat a lot of skunk cabbage, despite the fact that the plant contains oxalic acid, a poisonous compound. Humans that have tasted skunk cabbage claim that the plant burns their mouths for hours, but it doesn’t seem to bother deer. Deer are also able to tolerate other toxic plants, and it is possible that their gut bacteria can neutralize the toxins in these noxious plants.[7] During the spring, Sitka black-tails may be found from sea level to approximately 1500 ft., where they forage new plant growth as the snow line recedes. Deer continue to disperse into the higher altitudes as the snow melts, and they can be found anywhere from sea level to 3000 ft. in the summer. After the first frosts in mid to late September, the forage plants die, and the deer move out of the high elevations. The breeding season, or rut, begins in mid October and runs through November, and once again, the deer can be found from sea level to 1500 ft.[8] Depending on snow accumulation, Sitka black-tails usually descend below 1000 ft. in the winter. Their distribution is greatly influenced by the changing snow depth. During periods of heavy snow, many deer congregate on the beach or in heavily timbered areas at low elevations.[2] Deer are good swimmers, and at any time of the year, Sitka black-tailed deer can be seen swimming across the long, narrow bays on Kodiak Island. |

| Does begin breeding when they are two and continue to produce fawns until they are ten to twelve years old. Does as old as fifteen usually don’t produce any offspring. Does between the ages of five and ten are in their prime and usually produce two fawns a year.[2] Mating season on Kodiak occurs between mid October and late November. The gestation period is six to seven months, so fawns are born from late May through June.[1] Twins are the most common, although many young does only produce a single fawn, and triplets do sometimes occur. Newborn fawns weigh between 6.0 and 8.8 lbs. (2.7 to 4.0 kgs.). For the first week, a newborn fawn has no scent, allowing the mother to leave the fawn hidden as she browses for food to rebuild her energy reserves after giving birth.[1] |

|

|

Deer communicate with each other with the aid of pheromones produced by the scent glands located on the lower legs. A gland on the outside of the lower leg produces an “alarm” scent, a gland on the inside of the hock produces a scent to help deer recognize each other, and glands between the toes leave a scent trail when a deer travels.[1] Deer have excellent senses of sight, smell, and hearing. Their ears move independently of each other, allowing them to pick up on signs of danger from different directions.[1] |

|

|

Sitka black-tails have an average life span of ten years, and the mortality rate for fawns is between 45% and 70%.[1] Severe winters are the number one threat deer face on Kodiak Island. During mild winters with moderate temperatures and little snow accumulation, the deer population increases, but a harsh winter can cause a dramatic population decrease.[4] In contrast, limited, dispersed hunting pressure seems to have little effect on deer numbers in most areas.[4] Logging in Southeastern Alaska has destroyed areas that were once prime deer habitat,[1] and logging on the north end of Kodiak Island has undoubtedly effected deer habitat and deer populations in that area. A number of parasites and diseases have been found in Alaskan populations of black-tailed deer. Of these, lungworm is the most significant parasite, mainly attacking deer under the age of two, and normally found in areas with a very dense deer population. Lungworm disease is believed to be especially deadly in deer malnourished and weakened by a harsh winter.[4] Chronic wasting disease (CWD), a fatal, degenerative illness that effects deer, moose, and elk populations, particularly in Colorado and Wyoming, has not yet been found in Alaska, but since the disease has spread to eighteen states and two Canadian provinces, wildlife managers are concerned about keeping it out of Alaska. The disease is believed to be caused by prions that accumulate in the brain, so since 2003, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game has conducted a CWD program funded by the USDA. Deer, moose, and elk heads, either provided by hunters or collected from road-killed animals are examined for the presence of the disease. To date, no evidence of CWD has been found in the state.[9] |

|

A certain percentage of deformed antlers are common in any deer population and may be produced as the result of an injury. Research shows that leg, pedicle, and velvet injuries can all lead to deformed antlers, and these deformities may be temporary or permanent.[6] A large number of deer in certain areas of Kodiak Island, particularly the Aliulik and Hepburn Peninsulas on the southern end of the island, display abnormal antlers with a bizarre shape, sharp tips, and retention of velvet well into the mating season. Research on these deer indicates that they are also sterile. At first, the problem was believed to be genetically linked due to the fact that the founder deer population on the island was so small that the population must possess a narrow gene pool. This theory, however, did not explain why the deer with the mutated antlers were mostly concentrated in one area of the island, even though there was nothing confining the deer to this area. A study published in 2005 carefully analyzed all aspects of the problem and concluded that the sterile deer with the malformed antlers were not the result of inbreeding but that the deer living in this area of the island must be ingesting something such as kelp or grass that is laced with estrogenic molecules that alter antler growth, transform testicular cells, and block the descent of fetal testes.[10] |

|

Deer are often seen in the town of Kodiak, and in more remote areas of the island where they rarely see humans, it is not unusual to have a deer walk right up to you. Bears sometimes kill deer weakened by a harsh winter, but in the summer, you often see Kodiak bears and Sitka black-tailed deer standing within a few feet of each other on a stream bank. With so much other food readily available, bears don’t seem interested in chasing and attacking deer, and the deer don’t seem to consider the bears a threat. Despite periodic winters with heavy snowfall and frigid temperatures, sometimes so extreme that half the deer population on the island dies, and despite the narrow gene pool resulting from the small founder population; nearly ninety years after Sitka black-tailed deer were first introduced to Kodiak Island, the population has endured and appears to be healthy. |

|

|

References Cited 1. Wikipedia. Black-tailed deer. Available at: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black-tailed_deer

2. Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Sitka Black-tailed Deer (Odocoileus heminous sitkensis). Available at: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=deer.main

3. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge. Sitka Black-tailed Deer (Odocoileus hemionus sitkensis). Available at: http:// www.fws.gov/refuge/kodiak/wildlife_and_habitat/deer.html

4. Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Sitka Black-tailed Deer. Available at: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/static/education/wns/sitka_blacktailed_deer.pdf

5. Buck Manager. Deer Hunting and Management. Stages of Antler Development in White-tailed deer. Available at: http://www.buckmanager.com/2008/05/20/stages-of-antler-development-in-white-tailed-deer

6. Pierce, Robert A., J Sumners, and E Flinn. 2012. Antler development in white-tailed deer: Implications for management. University of Missouri Extension, G9486, January 2012. Available at: http://www.extension.missouri.edu/p/G9486

7. Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Alaska Fish and Wildlife News. How Deer Eat Poisonour Plants. Available at: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_id=249

9. Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Alaska Fish and Wildlife News. Keep Chronic Wasting Disease out of Alaska. Available at: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_id=481

10. Veeramachanei, DNR, RP Amann, and JP Jacobson. 2006. Testis and antler dysgenesis in Sitka black-tailed deer on Kodiak Island Alaska: Sequela of environmental endocrine disruption? Environmental Health Perspectives, 114(Suppl 1): 51-59. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1974179/

|

Copyright 2012 Munsey's Bear Camp